Wine Culture Magazine

The Naramata Bench is characterized by silty soils that were former lake bottom and exposed gravel and bedrock at higher elevations. Getty Images photo

It may seem strange to the casual observer how a fascination with wine very quickly turns into an enthrallment with dirt. Knowing heads nod slowly when they taste the tickle of electric acidity that has been thrust into the DNA of a steely Chablis or the dusty, fine-grained iron red tannins that coat the mouth from a Coonawarra Cabernet Sauvignon. Tasters thrive to make this link to the very dirt in which a vine grows, a link that somehow makes a wine complete by tracing it back to where it comes from.

Scientists, however, are not so enthusiastic. Without an established proven link between the makeup of a soil and the flavours in the wine, they take on the mentality that if it can’t be proven, then it doesn’t exist.

So, is our allure with the complexities of some mud and sand misplaced?

Skilled blind tasters around the world who can correctly pinpoint a wine’s whereabouts from sensations that seem to be driven by differences in soil aren’t giving up. They now have studies backing them up, too, showing that tasters can detect things like minerality in wine. Science just hasn’t figured out how it links with soil yet.

Here in B.C., we are increasingly fascinated with exploring the link between our diverse soils and tastes in the wine. It is now more common to find a winemaker neck deep in a soil pit rather than playing around with shiny tools in their cellar. We are starting to think more about the dirt, what it gives to the wine and even developing sub-GIs (Geographical Indications) to capture unique bits of terroir.

B.C. is also not some wasteland New World region of monotonous terrain, but enjoys an incredibly complex mixture of soils pushed by glaciers, raised from the ocean floor, deposited by meltwaters gushed from retreating glaciers, spewed from ancient volcanoes and dumped by water and gravity. There is a lot to explore and we are starting to identify some pockets with consistent personalities across the province.

B.C.’s wine regions are gifted with some pretty diverse and interesting terrain, landforms and soils. Next time you are raising a glass of B.C. wine, look into where it came from and start thinking about the dirt.

Cowichan Valley Sub-GI

Retreating glaciers and the uplifting of the ocean floor of up to 100 metres above sea level left behind marine sediments, glaciofluvial sediments and glacial till.

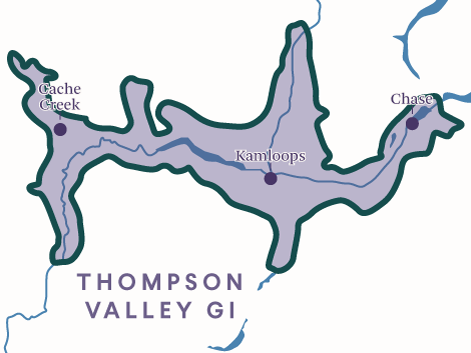

Thompson Valley GI

Limestone-rich benches give steely minerality to the wines produced around Kamloops.

Similkameen Valley GI

Alluvial fans, high levels of calcium carbonate and a wisp of volcanic ash at depth contribute to wet stone mineral notes and crisp acidity.

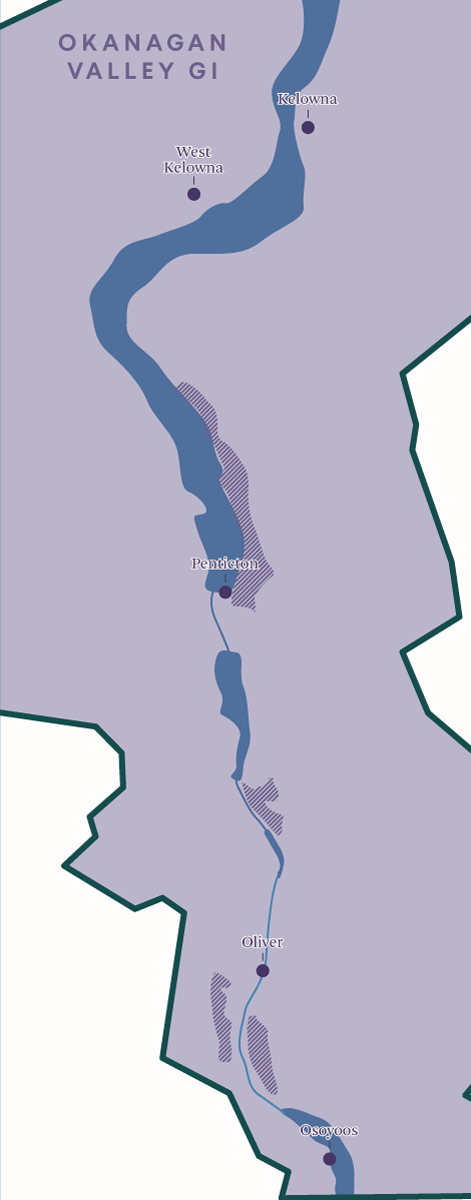

Western Okanagan Valley

Glaciers eroded 50-milion-year-old volcanos along the west side of the Okanagan Valley, producing soils enriched in basalt rocks.

Naramata Bench GI

Silty soils that were former lake bottom and exposed gravel and bedrock at higher elevations.

Okanagan falls GI

Kettles formed when huge blocks of ice fell off a glacier and later melted, leaving kettle holes behind and a jumbled array of ridges and mounds.

Black Sage Gravel Bar

Calcium carbonate seams giving stony minerality.

Golden Mile Bench GI

Coarse textured sand and gravel fans all formed from Mount Kobau.

Black Sage Bench

Deep sandy soils deposited from the collapse of an ice dam about 10 million years ago.

Rhys Pender is a Master of Wine who combines his time writing, judging, teaching, consulting and dirtying his boots at his four-acre vineyard and winery, Little Farm Winery, in the Similkameen Valley.

Rhys Pender is a Master of Wine who combines his time writing, judging, teaching, consulting and dirtying his boots at his four-acre vineyard and winery, Little Farm Winery, in the Similkameen Valley.

Copyright © 2025 - All Rights Reserved Vitis Magazine