Wine Culture Magazine

Getty Images photo

It’s easy to become blithe about the juggernauts of the wine world. The prevailing interest in lesser-known wine regions, arcane grapes, regenerative farming and ultra-lo-fi winemaking is widely covered by the wine press. And while I love and support all things obscure, esoteric and low intervention, I love it even more when these philosophies materialize in mainstream, conventional wine regions. Like California, for instance. A recent trip was quite revealing.

California is the world’s fourth largest wine-producing region, with 248,881 hectares (615,000 acres) of wine grapes, and the global leader in sustainable winegrowing. A staggering 85 per cent of California wine is made in a certified sustainable winery (that’s 258 million cases each year from 250 wineries), and 60 per cent of planted vineyards are certified.

While there are several protocols to choose from, most have adopted the statewide program called Certified California Sustainable Winegrowing (CCSW). Sustainable wine growing covers the obvious areas of water and energy efficiency, soil health, preserving wildlife habitats, pest and waste management—all crucial points in responsible farming, and vital steps towards organic and biodynamic viticulture. But in its code, the CCSW places the same emphasis on people and prosperity as protecting the planet. To become certified, wine companies have to consider areas like housing, health care, education and social services for their workers.

The buy-in from the California folk is palpable. They are farming regeneratively, using natural ways to manage pests, setting land aside for habitat rehabilitation, reusing and recycling in the tasting rooms—and growing a gamut of grapes, officially 125 varieties now, not just Cab and Chard. Perhaps most important is the dialogue and human connection that has resulted. People are talking and sharing, and many winemakers told me that positive peer pressure (the encouraging kind!) is now the driving force behind the sustainability cause.

This photo taken at Emeritus’ Hallberg Ranch Vineyard in January shows the point where the roots stopped when the vines were irrigated (upper arrow), and the extra depth the roots grew, searching for water, after conversion to dry farming (lower arrow). DJ Kearney photo

More wineries are leaning into the notion of dry farming in the face of the state’s repeated drought cycles. The recent 12 atmospheric river events have refilled water reserves dramatically, but future droughts are a certainty. There is plenty of evidence that the more water-dependent the vines, the more stressed they can become in a dry spell, and they can often show more stress after irrigation than if they’d never received water. It’s a vicious cycle that has prompted some wineries to stop tilling their vineyards and plant cover crops, the two main ways to manage evaporation and water retention.

Others, more radically, have converted to dry farming.

Of course, you need the right water-retaining soils (like clay loams) and steady nerves, perhaps, but California has a good number of unirrigated vineyards as inspiration. Among them are the classic old vineyard blocks in Lodi, Amador and Sonoma counties. Then there are wineries like Frog’s Leap or Dominus, which have dry-farmed from the get-go.

Emeritus Vineyards in the Russian River Valley converted its Hallberg Ranch vineyard to a dry farming regimen over a decade ago. Relying only on winter rainfall and the water holding capacity of its Goldridge soils, its vines adapted very quickly with little loss in bunch size or yield. The wines showed the change immediately, with deeper colours, more intense flavours, and more terroir signature.

There are still just a few new dry-farmed vineyards in California (and around 30 in Oregon), but the conversations are happening.

The Monarch electric tractor rolls into a clean-energy future. Photo courtesy of Monarch

Look out for this nimble number in the future: the Monarch MK-V electric, driver-optional, smart farm tractor. A world first, this Livermore-based tractor company did some trialling at another Livermore pioneer, Wente.

Comparing a John Deere diesel tractor and the Monarch electric model, Wente was able to quantify the annual savings in fuel and emissions, based on an average run time of 1,000 hours per tractor. Wente’s number-crunching findings? The Monarch had the competitive edge, with both massive estimated annual fuel cost savings and emissions reductions. And the Monarch finished with 24 per cent battery charge remaining.

This clean energy comes with a US$89,000 price tag, but as Melanie McIntyre of RAEN vineyards points out, it’s highly versatile and powerful, you can roll it up to a winery and essentially plug the winery into it, using the tractor as a clean power generator. Fully autonomous, it can make hairpin turns and it’s slim enough for narrow rows of vines. It’s an important, sustainable start that’s generated lots of talk.

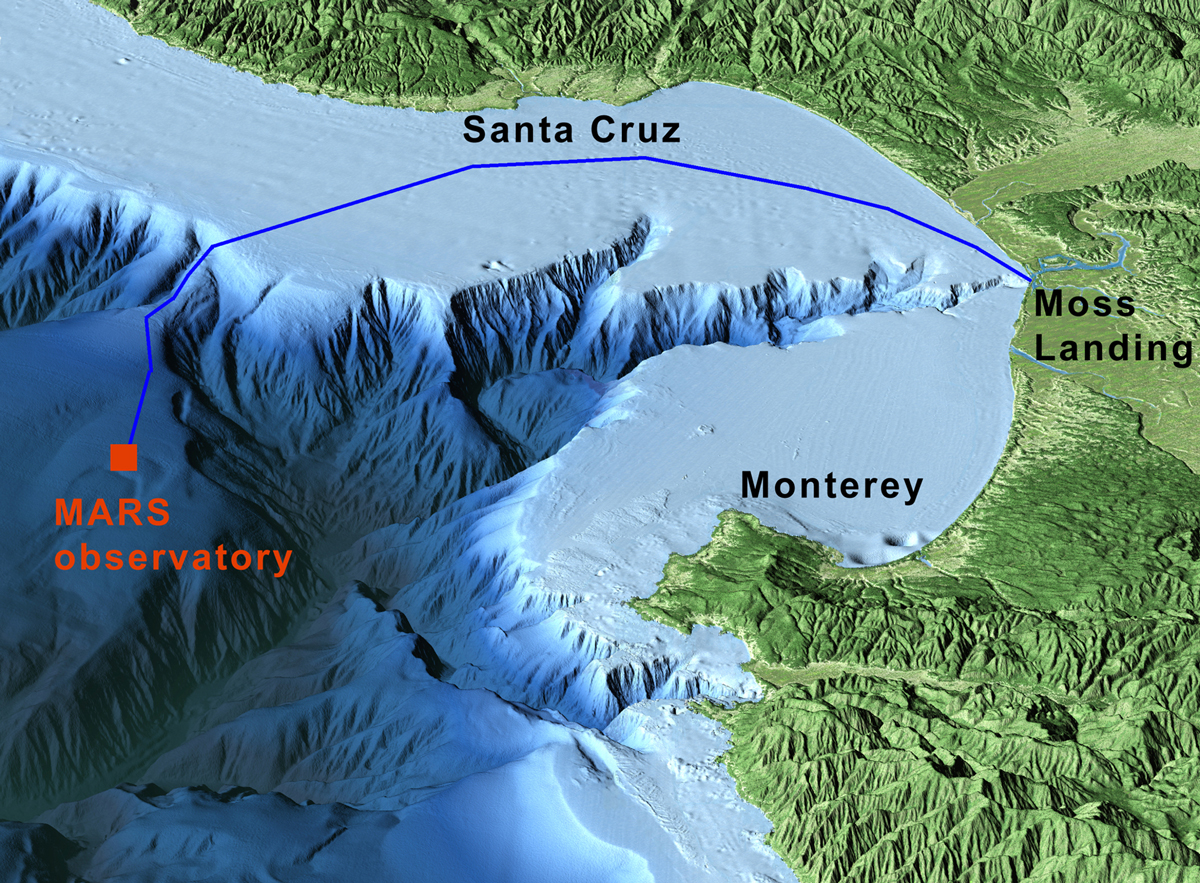

Nicknamed the Blue Grand Canyon, the Monterey Submarine Canyon hits depths of 3,500 metres (think Grouse Mountain times three) and its cold waters profoundly affect the climate of the Santa Cruz, Monterey and Santa Lucia Highlands wine regions.. Copyright David Fierstein © 2000 MBARI

California wine is defined by superlatives, ranging from the extremes of neutral bulk vino to profound, terroir-dripping wines. In between is everything from the fighting varietals to colossal brands to cult wines with prices that take your breath away.

Since the fame and attention that came in the wake of the 1976 Paris tasting, Californians have gone enthusiastically around the world promoting their wines, showcasing wines extravagantly ripened under golden sunshine.

Over the last decades, Californians have studied their soils, expanded the appellation system, and done all the work that maturing wine regions do. But now the perspective has undergone a massive shift.

This new perspective recognizes that the three-dimensional shape of the state dictates wine styles in a way far beyond the influence of grape variety, ubiquitous sunshine, latitude or temperature indexes.

Four features can account for wine style and quality in California, and this is the new education thrust rolled out recently by the Capstone Wine Certification program.

• Coasts: Ultra cool-climate regions like the new West Sonoma Coast AVA, where icy ocean upwelling, fog, cloud cover and salty air leave a clear stamp on style.

• Rivers and deltas: Intricate waterways, canals and sloughs that connect major rivers and create unique soil environments also create pathways for cooling ocean influence

• Gaps: Openings in the Coast Mountains, typically incised by rivers, allow the ingress of cooling fog, wind and cloud cover. They include Petaluma Gap, Chalk Hill Gap, Templeton Gap and Rainbow Gap.

• Mountains: Planting on the foothills and high elevation sites creates distinct flavour profiles and tannin structures.

More than simple latitude and temperature indexes, mountain building, deep sea trenches, surface water and geological history are the shaping forces that reveal and explain California wines.

DJ Kearney is a Vancouver-based wine educator, consultant, speaker, judge and global wine expert. Creator of the New District Wine Club, she is also Terminal City Club’s Director of Wine and Vice-President of CAPS-BC, responsible for the Best Sommelier of BC competition.

DJ Kearney is a Vancouver-based wine educator, consultant, speaker, judge and global wine expert. Creator of the New District Wine Club, she is also Terminal City Club’s Director of Wine and Vice-President of CAPS-BC, responsible for the Best Sommelier of BC competition.

@ Vitis Magazine