Wine Culture Magazine

Getty Images photo

Sparkling wine is what I drink while deciding what I’m going to drink with dinner. —Harry McWatters

There was no greater champion of B.C. sparkling wine than the late Harry McWatters. Before launching Sumac Ridge in 1979, McWatters cut his teeth in sales at Casabello Wines. There he learned the importance of being able to offer a balanced portfolio that spanned red and white as well as sparkling wines. It was a mantra he heartily embraced, even serving ice wine at every opportunity. Hence, once he’d established his “bread and butter” products—such as Sumac Ridge Private Reserve Gewürz, once B.C.’s biggest selling homegrown white—McWatters wasted little time in laying down his first brut wines.

Much of the impetus flowed from his conviction that conditions in the cooler central Okanagan (which he regarded as the triangle between Summerland, Naramata and Okanagan Falls) produced grapes with ideal levels of acidity necessary to make good sparkling.

McWatters and others drew on trials at Summerland Research Station, which also aided in the early development of traditional method wines by other early luminaries Blue Mountain and Cipes/Summerhill. Sumac Ridge released its inaugural Steller’s Jay brut in 1989.

McWatters’ choice of the protected provincial bird as his sparkling wine brand was somewhat tongue in cheek. Jays are fearless and known to have voracious appetites for ripe grapes. McWatters purchased Le Comte Estate (later Hawthorne Mountain Vineyards, now See Ya Later Ranch) from Albert Lecomte, who also made sparkling wine. Legend has it that Lecomte’s solution to the Steller’s Jay problem was simple: shoot them. Evidently, he could be a tad careless; one day he managed to take out not only a few birds but also the sole power line to Okanagan Falls.

The late Harry McWatters was an early proponent of B.C. sparkling wines, and believed they were the future of the wine industry. Darren Hull photo

A few decades on, McWatters’ triangle theory has proven to be more than just a hunch. Excellent traditional method, Charmat style and other effervescent wines are indeed being made with fruit sourced primarily from “the triangle.” Stalwarts like Blue Mountain have been joined in Okanagan Falls by Noble Ridge, Stag’s Hollow, Blasted Church and Meyer, who produce myriad styles.

Naramata Bench is home to traditional method specialists such as Bella and Township 7’s Seven Stars (whose Equinox scooped Best Canadian Sparkling Wine at London’s prestigious 2019 Champagne & Sparkling Wine World Championships). On Okanagan Lake’s mountain-shaded west shore, the Fitzpatrick Family have transformed Greata Ranch into a spectacular traditional method destination. Newer Sumac sparkling neighbours in Summerland include Haywire/Narrative, Lightning Rock, 8th Generation and Giant Head, while in Penticton, Time Family of Wines makes a range of styles under the Chronos, Evolve and namesake legacy McWatters labels.

Both in the Okanagan and elsewhere, the potential for sparkling wines is growing. In part the result of climate change, McWatters’ initial triangle has expanded significantly north to include the south and East Kelowna benches, where Tantalus (making Riesling, blanc de blancs and Pinot Noir) and Sperling are established traditional method producers, with Quails’ Gate planning to make sparkling wines with fruit off its new, southside planting not far from pioneering Summerhill.

In Lake Country, Gray Monk is a mainstay original traditional method producer, while neighbouring Intrigue continues to expand its Charmat range. Still further north, fledgling O’Rourke Family Estate has just released its first traditional method wine while further north still 50th Parallel enjoys continued success with its traditional method blanc de noir and Glamour Farming Charmat bubbles. Given the results so far, it seems likely the “up north” west side of Okanagan Lake also has serious sparkling potential.

Sparkling is also ascendant well beyond the Okanagan, both in the Fraser Valley and on Vancouver Island, where producers such as Averill Creek, Blue Grouse, Unsworth and Venturi-Schultze are pacesetters.

Blue Mountain Vineyards was among B.C.’s early pioneers in sparkling wine. Getty Images photo

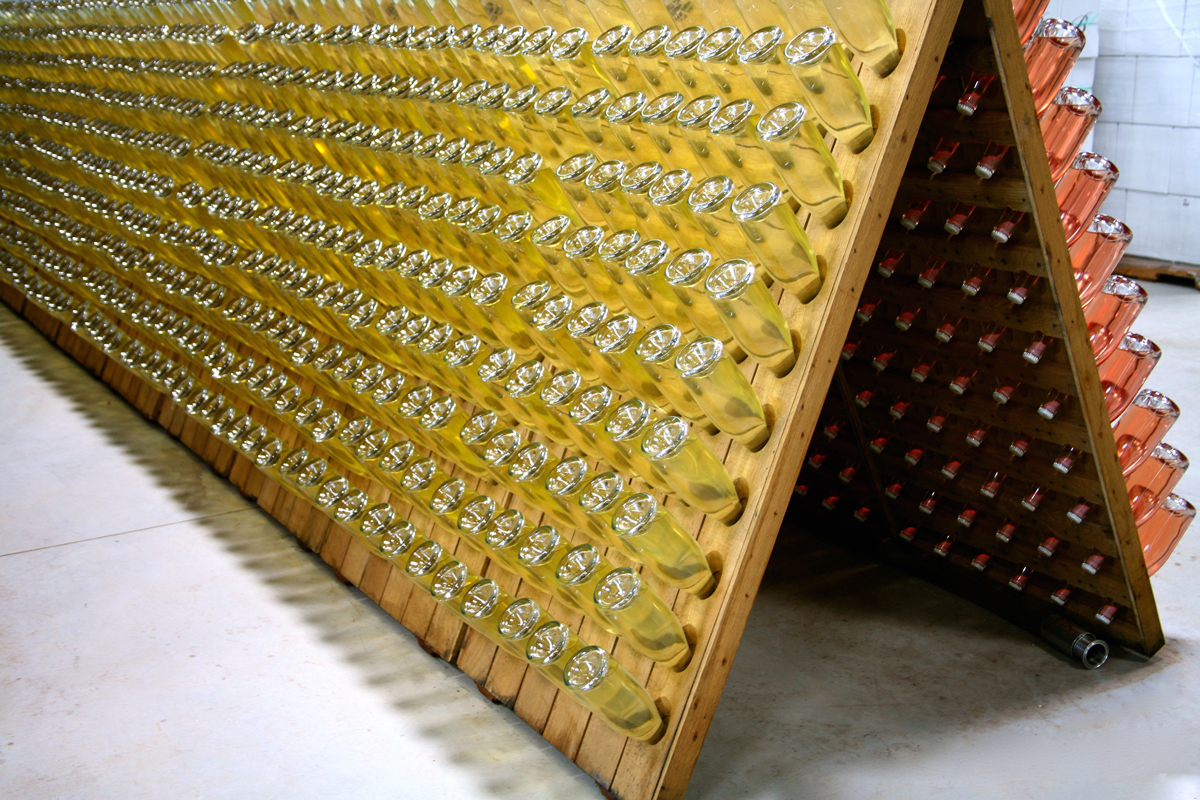

B.C.’s initial sparkling wine success was driven entirely by traditional method (bottle-fermented, hand-riddled and disgorged) wines. However, more recently winemakers have been turning to more economical and less labour-intensive methods, such as the closed tank system used in Prosecco. Italian sparkling wine production has almost tripled in a decade, a feat that would have been impossible were it not for the Italian Marinotti technique developed in 1895 and improved upon by France’s Charmat in 1907.

The Prosecco phenomenon has not gone unnoticed in B.C., where international sparkling wine sales have gone through the roof in recent years. While Charmat wines may not yield the complexity of their traditional method counterparts, their larger volume potential with much quicker return on investment—as well as increasingly sophisticated styles—are proving popular with winemakers and consumers alike. Interestingly, they’re also serving to enhance the reputation of traditional method B.C. wines, some of which are seeing significant price increases.

As younger wine drinkers explore their options, wineries have been quick to respond by offering different formats and lower alcohol wines, especially in the form of lightly sparkling piquette in cans. Low in alcohol, piquette was traditionally made by adding water to grape pomace after pressing, and was often quaffed with lunch by farmworkers in the fields. Its popularity in B.C. is very much on the rise, as evidenced by piquette-inspired drinks (in bottle and in can) from the likes of Birch Block, Averill Creek, Tantalus and many more.

The low-alcohol and can options are also gaining ground in restaurants. Witness the wine list at chef Angus An’s Fat Mao Thai noodle house, which features solely wine or piquette in cans (the one exception being Orofino’s Gamay MagBag). In addition to providing some smart pairing choices (Averill Creek Gewürz-based piquette with hot and sour seafood noodles), the 375 mL can is just perfect for lunchtime sharing.

Many rows of white and pink sparkling wine sit neck down in the riddling racks inside a winery. The bottles are turned slightly every day to help the sediments settle in the narrow neck, for removal before final capping. Getty Images photo

The Spanish have cava, the Germans their sekt, Italians Prosecco and the French, of course, Champagne, Crémant, Blanquette and everything in between. Even the Brits (who arguably pop more corks than anyone else) are toying with the notion of naming their burgeoning “fizz” something other than, well, “bubbles.” (Unsurprisingly, “Britagne” proved to be a non-starter.) Yet we Canadians stoically march on with such riveting monikers as traditional method—which we also lazily lump in as just another sparkling wine.

Part of our problem, on the one hand, is that we really don’t like copying others—sometimes. On the other, there have been moments when we’ve been remarkably adept at shameless imitation with unabashed flattery.

Back in the 1970s, Baby Duck was Andres’ low-alcohol knockoff of a Michigan sparkly semi-sweet red named Cold Duck (itself borrowed from an old German custom of blending cellar ends). It was also not far removed from Britain’s immensely successful Babycham (a perry, as in pear cider), whose 1960s TV ads featured a Bambi-esque deer leaping in and out of Champagne cups with a slipstream of twinkling stars.

However, kudos to those Vancouver Island folks who at least had the smarts to coin highly original Charme de L’île for their Charmat sparklers. But when it comes to doing justice to our truly worthy traditional method wines, isn’t it time we Canadians came up with something just a little bit more exciting?

Blasted Church OMG 2018

(Skaha Bench, B.C., $30) Toasty, bright acidity, citrus, good length.

McWatters Collection Brut 2017

(Okanagan Valley, B.C., $65) Brioche, apple citrus through a rich palate, lemon close.

Narrative XC 2022

(Okanagan Valley, B.C., $25) Luscious tropical notes, creamy lengthy palate.

Noble Ridge The One 2017

(Okanagan Falls, B.C., VQA, $40) Toasty brioche, orchard and stone fruit, mineral and zest.

Tantalus Blanc de Noir 2020

(East Kelowna Slopes, B.C., $35) Red apple, cherry, rhubarb, mineral and brioche.

Unsworth Charme de L’île Rosé 2018

(Vancouver Island, B.C., $29.90) Red berries, raspberry, cranberry, crisp and dry.

Tim Pawsey writes and shoots at hiredbelly.com as well as for publications including Quench, TASTE and Montecristo. He’s a frequent wine judge and is a founding member of the B.C. Hospitality Foundation.

Tim Pawsey writes and shoots at hiredbelly.com as well as for publications including Quench, TASTE and Montecristo. He’s a frequent wine judge and is a founding member of the B.C. Hospitality Foundation.

Copyright © 2026 - All Rights Reserved Vitis Magazine