Wine Culture Magazine

Scannable chips will be integrated into the top layer of Parmigiano Reggiano cheese. Photo courtesy of Parmigiano-Reggiano Consorzio

It’s well established that wine bottles have means for fraud and counterfeit protection, including special inks, holograms and computer tagging. Now the food industry has joined in with high-tech, food-safe microchips.

Why? Well, just like designer handbags and fine wine, the premium cheeses of the world are becoming the objects of fraudulent imitation. It’s no surprise that the king of cheese, Parmigiano Reggiano, has been the first to take action.

The Consorzio del Parmigiano Reggiano actually used the Canadian market to make the final decision to trace food. The study they co-conducted showed that 84 per cent of Canadians emphatically want to know where their food comes from, and only 40 per cent believe any labelled claims. So along came the chip … as small as a grain of salt and entirely safe to eat.

Each wheel of Parmigiano Reggiano is wrapped in plastic casing with braille-like lettering that identifies it as authentic. Now researchers are testing whether a tiny microchip made of protein and embedded in the QR plate can prevent impostors. Supplied photo

The scannable digital labels are included in the casein rind of the cheese (the part not usually consumed) and should help thwart counterfeit versions that cost the legitimate industry billions of euros.

There are dozens of regionally protected foodstuffs (truffles, peppercorns, saffron, sausages, hams, olives, even breads) that might follow suit, embedding traceable microchips to ensure consumer safety, quality and, perhaps most importantly (and just like wine!), provenance.

Chemical physicist Gérard Liger-Belair, professor and Champagne researcher at University of Reims Champagne has helped the world understand the science of bubbles. Photo courtesy of Gérard Liger-Belair

Have you ever pondered bubbles? The drinkable kind, of course, in sparkling wine, beer, colas, carbonated water… any beverage that contains dissolved carbon dioxide gas. (Make ours Champagne!) A remarkable chemical physicist (and member of an acclaimed Burgundian wine family) has made bubbles the object of his study for decades now, starting with his PhD. Gérard Liger-Belair’s findings have helped the world understand the fizzy wonders of Champagne, as well as sea spray, cloud formation and hydrogen bubbles on Saturn’s moon, Titan.

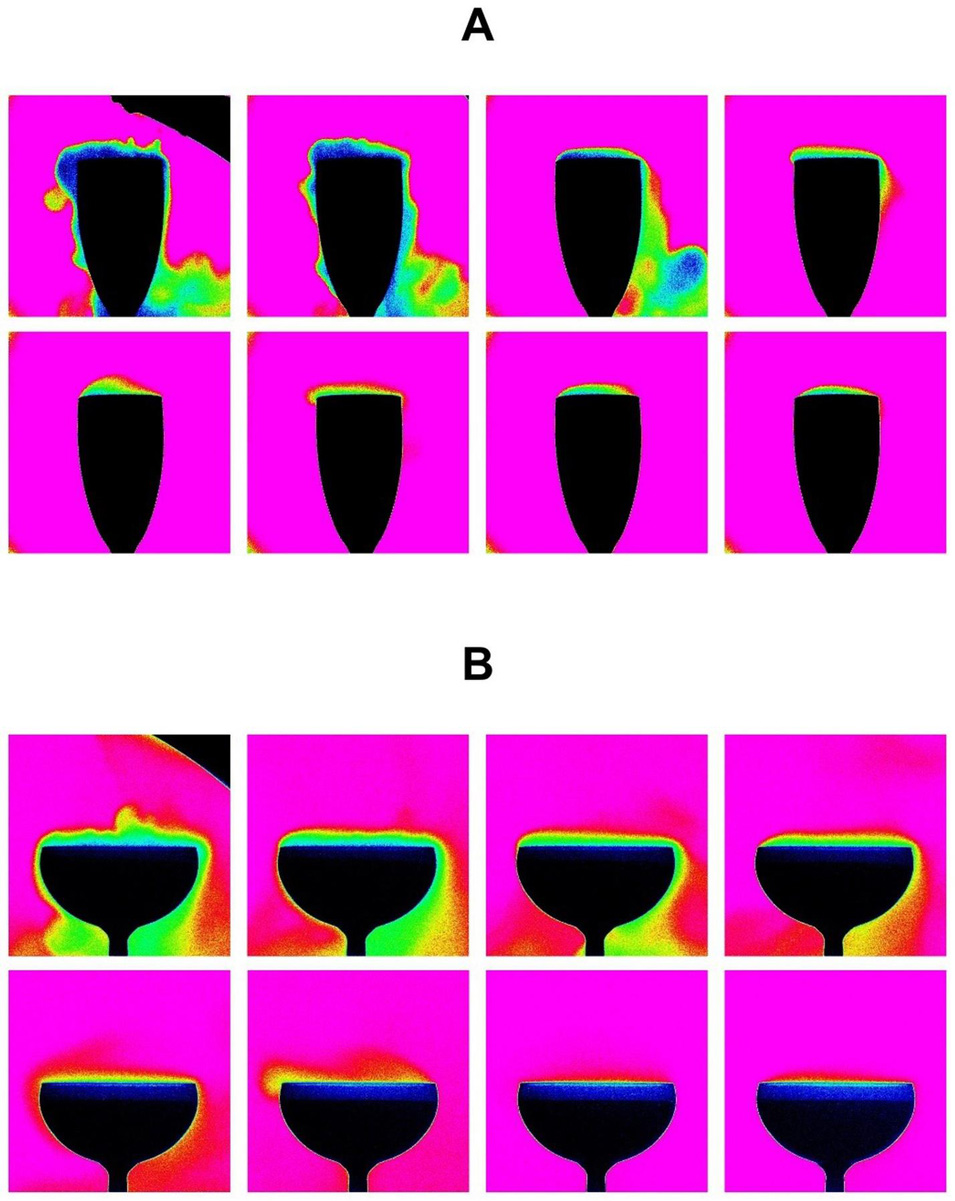

Micro-gas chromatography shows the loss of carbonation in sparkling wine when it is served in a coupe versus the flute. Source: The Verge

Try dropping some of his fizz tidbits at your next social gathering, especially if bubbles are served:

• Liger-Belair has calculated there to be about 10 million potential bubbles in a 750 mL bottle of Champagne.

• A good sparkling wine cork (one that is made of small cork particles and adhesive) will keep bubbles in the bottle for at least 70 years (if you can be that patient).

• The number of bubbles that actually form in the glass is a complex interaction between dissolved CO2 gas, minute gas pockets trapped within particles acting as bubble sites, and ascending bubble dynamics.

• Your pouring technique definitely matters—pouring straight down into a flute (just as you would pour still wine) will give you about a million bubbles in a 100 mL glass. But employ a beer-style pour down the side of the glass, and you’ll get to enjoy tens of thousands more bubbles. By tipping the glass, you are preventing the bubbles from bursting on impact.

• For maximum bubbles, make sure you avoid soap on your Champagne glasses. Soap is a surfactant and quells carbonation; conversely, polishing with a soft cloth will boost bubble creation as the microscopic dust and fabric filaments left inside the glass will act as a site for bubble formation.

• Pre-etched sparkling wine glasses have a nucleation site invisibly scratched into the bottom of the glass by a laser.

• Coupe or flute: Gas chromatography has definitively shown that the coupe loses CO2 gas and therefore bubbles a third faster than a flute.

• Warmer sparkling wine is fizzier; thorough chilling depresses carbonation and results in fewer bubbles forming.

Drink wine, get stoned

Drink wine, get stonedThere are stony wines, and then there are stone labels. Only a few wineries have adopted eco-friendly stone paper labels, but look for that to change.

About as sustainable as it gets, the mineral paper production process uses no trees, no water and no chemicals. It requires significantly less energy in manufacturing and is endlessly recyclable. Additionally, stone paper does not generate any toxic emissions during incineration and degrades under UV light. It’s chlorine-free, grease-proof, tear- and weather-proof. Stone paper labels stand up well in an ice bucket, too.

They can be made from mining waste products or raw stone crushed into powder, mixed with a non-toxic and recyclable binder, and rolled into something that looks and feel just like, well, paper. A German printing company is even including recycled polythene. The concrete-crazy folks at Summerland’s Okanagan Crush Pad use stone labels in their Free Form range. and a smattering of wineries around the world have also joined this eco-friendly movement.

Can you imagine 302,832,942 litres of wine flowing into industrial stills across France?

The world’s second-largest wine producer (just behind Italy) is set to destroy the equivalent of 100 Olympic-sized swimming pools, helping to deal with a huge surplus of vin. Surplus because people are buying less and drinking less. From a peak in 1926 of 136 litres of wine per capita to just 40 today, it’s clear the French are choosing beverages other than wine.

The European Union and French government have stepped in to fund the destruction and prop up prices by limiting quantity. Over €200 million are being doled out to producers to distill their excess wine into pure alcohol, allowing them to sell it for everything from perfume to cleaning products and hand sanitizer.

This buyback program has happened before, but watch out for long-term strategies like production controls and funded vine-pull schemes. This past June the government revealed it would fund an uprooting of 9,500 hectares of vines in Bordeaux, at the cost of €57 million. Other crops are being encouraged instead. Perhaps the future will see olive oil instead of Côtes du Rhône and hops rather than Saint Émilion!

DJ Kearney is a Vancouver-based wine educator, consultant, speaker, judge and global wine expert. Creator of the New District Wine Club, she is also Terminal City Club’s Director of Wine and Vice-President of CAPS-BC, responsible for the Best Sommelier of BC competition.

DJ Kearney is a Vancouver-based wine educator, consultant, speaker, judge and global wine expert. Creator of the New District Wine Club, she is also Terminal City Club’s Director of Wine and Vice-President of CAPS-BC, responsible for the Best Sommelier of BC competition.

Copyright © 2025 - All Rights Reserved Vitis Magazine