Wine Culture Magazine

The spiral staircase at Martin’s Lane Winery follows the Fibonacci sequence to mimic vine growth. Nic Lehoux photo for Martin’s Lane Winery

There is no tasting room sign. No parking area for tour buses. And, apparently, no entrance. But just as we’re almost ready to give up, a towering slab of blackened steel swings slowly, silently open.

And with that, we’ve entered Martin’s Lane Winery.

Designed by Seattle-based architect Tom Kundig of Olson Kundig, this is quite possibly the most beautiful winery in British Columbia. Certainly, it’s the most technologically advanced, and the only one that’s home to a giant Douglas Coupland-designed bronze sculpture of Vincent van Gogh’s head.

“It’s the most ambitious Pinot Noir winery in the world,” says Martin’s Lane winemaker Shane Munn. “He [owner Anthony von Mandl] has given me everything I need to make great wine.”

B.C., it turns out, makes not just beautiful wine, but beautiful wineries.

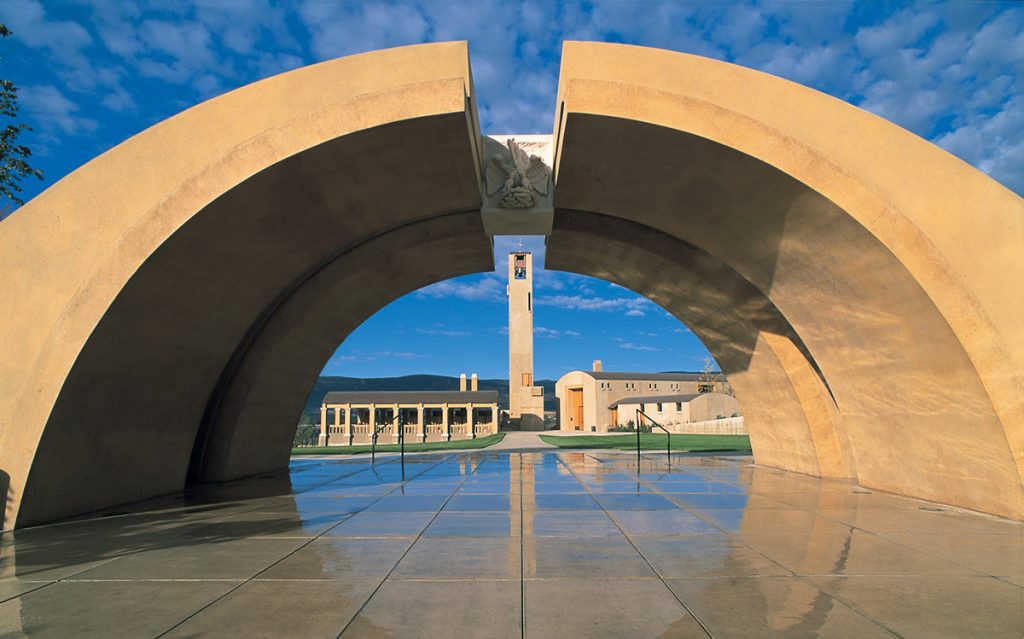

The arch at the entrance to Mission Hill Family Estate in West Kelowna frames the winery’s signature bell tower. Mission Hill Family Estate photo

Back when B.C.’s wine industry emerged in the 1980s and ’90s, tasting room designs leaned toward the rustic, to alpine chalets and Tuscan farmhouses and the occasional Quonset hut with a plywood counter. Then, in 1996, inspired by Robert Mondavi’s Napa Valley winery, Anthony von Mandl hired the then relatively little-known Kundig to design Mission Hill Family Estate in West Kelowna, and nothing would be the same again.

He’s alongside Frank Gehry as the greatest contemporary architect in North America

Kundig elegantly combined contemporary simplicity with traditional elements such as the 85-foot-high bell tower and Parthenon-like outdoor restaurant, all clad in board-formed concrete that gleams in the Okanagan sun. Mission Hill is still considered a landmark of winery design. In August, it was the only Canadian winery named to Architectural Digest magazine’s roundup of the world’s 19 most beautiful wineries, along with such dramatic structures as the fantastical Frank Gehry-designed Marqués de Riscal in Spain.

It also set a new standard for other B.C. wineries. Gradually, the simple huts and quaint farmhouses gave way to sleek contemporary designs, to the LEED-certified minimalism of Tantalus, the dark drama of 50th Parallel Estate and the West Coast modernism of Black Hills or Fort Berens.

Meanwhile, Kundig has become one of the most famous architects in the world. “He’s alongside Frank Gehry as the greatest contemporary architect in North America,” Munn says.

In an expression of elegant symmetry, two decades later von Mandl invited him back to the Okanagan to take on Martin’s Lane.

Martin’s Lane Winery is designed as a sloping rectangle that pays homage to its place in the natural environment. Nic Lehoux photo

Tom Kundig is the architect of both Mission Hill Family Estate and Martin’s Lane Winery. Martin’s Lane Winery photo

“A lot of Tom’s work, under Anthony’s direction, is that this winery has a sense of place,” says Munn as we step through that big steel door. “This room here sums up Tom’s architecture. His work is very tactile and very textured.”

The building, which took two and a half years to complete, was designed to represent the environment of rocky, sun-baked hills surrounding it. It slopes dramatically down the hill above Cedar Creek, conceived as a fractured rectangle in glass, corrugated Corten steel and concrete.

Inside the entranceway, the walls are covered in the same board-formed concrete as Mission Hill. Ahead of us, a spiral staircase leads to a welcoming hospitality area, all warm woods and comfortable furnishings, designed by Antonio Puig of the Barcelona interior design firm GCA Arquitectos Asociados. “Antonio designed the hospitality area like it was the winemaker’s home,” Munn says.

Puig also created the sculptural steel entry door, which weighs more than 1,200 pounds, but can be opened gently with just two fingers. Its blackened steel pays poignant homage to the burnt trees that remain from the devastating 2003 forest fire that singed the edge of the property.

Nothing has been left to chance, from the white glass-topped tasting table that, at just the right angle, is revealed to be wine red, to the hand-blown glass light shades in the private dining room that are meant to resemble Riesling grapes.

“We’re trying to make this a pretty cool experience,” Munn says. Mission accomplished.

Even the technology-driven barrel room at Martin’s Lane Winery is designed as a work of art. Nic Lehoux photo

Of course, a winery can’t just be a cool experience. It also has to be a functional one.

Everything in here, whether it’s refrigeration or lighting, it’s connected by phone. It’s a very technology-driven winery that allows me to do nothing to the wines.

It’s nice to have a beautiful tasting room, but a winery also needs a crush pad where the grapes are unloaded during harvest, room for fermentation tanks, storage area for barrels and space for a bottling line. At most wineries, these areas are utilitarian at best.

Not at Martin’s Lane.

Everything here is designed around the single-vineyard Riesling and Pinot Noir that are the only wines Martin’s Lane produces. “I choose to have a minimalist approach to winemaking,” Munn says. “Pinot, you talk to any winemaker that focuses on Pinot, it’s a very sensitive variety that doesn’t like being manipulated.”

The juice flows naturally down each level so the wine is “gently made by gravity.” And technology is put to good use. “Everything in here, whether it’s refrigeration or lighting, it’s connected by phone,” Munn explains. “It’s a very technology-driven winery that allows me to do nothing to the wines.”

Even the barrel room is work of art, each barrel lined up with a laser and spot-lit with a light fixture that has its own IP address. “Tom designed the barrel cellar so the barrels would be part of the architecture,” Munn says.

There’s no question that Martin’s Lane will be raising the bar for winery design in the Okanagan just as Mission Hill did before it.

But don’t expect to just drop by and have that big steel door swing open for you. Tastings are by appointment only and are always a bespoke experience. “We want the experience to be quite personal,” Munn says. “If we get three or four visitors in a day, that’s a big day for us.”

And that, too, is by design.

Take a glance at just a few of B.C.’s most eye-catching wineries.

Jon Adrian photo

Liquidity Wines’ president Ian MacDonald is as well known for his love of art as for his love of wine. So it’s no surprise that he envisioned his winery as both a showcase for his art collection and as a work of art in itself. With a patio and infinity pool overlooking McIntyre Bluff, the tasting room and bistro are gleaming white and coolly modern. The concept was conceived and designed by MacDonald, realized by CeDeCe Design in Calgary and built by Ritchie Construction.

Jon Adrian photo

Proprietor John Skinner admits that when he started Painted Rock, he was fully focused on the wines, not where they were sampled. Not any more. Architect Dominic Unsworth of Kaleden’s Fallowfield Design + Development designed the one-storey tasting room as an elegantly futuristic building overlooking Skaha Lake. Not only does it make the most of its spectacular view, but it is clad in shimmering Alucobond, an aluminum composite material that subtly reflects the natural environment.

Derek Ford photo

Long gone is the quaint alpine hut in the Cowichan Valley. In its place is a swooping wood, glass and steel structure that is both sustainable and beautiful. Designed by Joe Chauncey from boxwood creative, the building features a closed-loop water system, geothermal heating, rainwater capture and other eco-friendly features. The shape of the building itself is an homage to the blue grouse: the roofline is inspired by the curve of the bird’s neck, the tasting room ceiling by the swell of its belly, the entrance by the blue hues of its tail feathers.

Vanessa Vineyard photo

Heading west from Osoyoos, it’s impossible not to notice the grandly brooding winery perched on a bluff just outside Cawston. Where most B.C. wineries lean to the bright and light, Vanessa Vineyards went as deep and dark as the inky reds it produces. The structure was designed by co-owner Suki Sekhon and general manager Sandeep Sangha, while Sara Patterson Design created the woodsy clublike interior.

Joanne Sasvari is editor of Vitis and The Alchemist magazines. She also writes about food and drink for WestJet and Vancouver Sun, and is author of the Wickaninnish and Vancouver Eats cookbooks.

Joanne Sasvari is editor of Vitis and The Alchemist magazines. She also writes about food and drink for WestJet and Vancouver Sun, and is author of the Wickaninnish and Vancouver Eats cookbooks.

Copyright © 2025 - All Rights Reserved Vitis Magazine